My Jewish Central New York

Join our mailing list

My Jewish CNY Subscribe

Follow Us!

ONONDAGA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION EXHIBIT

The Onondaga Historical Association has a permanent exhibit of Jewish contributions to Syracuse and Onondaga County on the first floor of its museum at 321 Montgomery Street. “From Laying the Foundation to Forging Ahead” documents the role of the Jewish community in advancing the social, religious, economic and political fabric of the city and county in four areas: community, business, entertainment and athletics.

The business section concentrates on Jewish-owned retail stores, factories, and other businesses such as Alex Lyon & Son, Flah’s, SYROCO, Oberdorfer Foundry and United Radio. Some of these businesses are still thriving in Syracuse and beyond. The next generations of these successful companies were interviewed recently, and their oral histories will be added to the exhibit itself.

This process was recorded and made into a short film featuring three families.

Books

From A Minyan to A Community: A History of The Jews Of Syracuse

B.G. Rudolph (1970)

The Jewish Community of Syracuse

Barbara Sheklin Davis and Susan B. Rabin (2011)

A Place That Lives Only In Memory: The Old Jewish Neighborhood of Syracuse, New York

William Marcus (2012)

History of the Jewish Federation of Central New York

I. In the beginning: 1918 – 1928

The Talmud (Shevuot 39a) says “Kol yisrael arevim zeh bazeh”—“All Israel is responsible one for the other.” This concept is the foundation of communal responsibility in Judaism. All Jews share an obligation to help their co-religionists and to ensure that their basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter are met. So when Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant reluctantly acquiesced to allowing 23 Jews into New Amsterdam “provided the poor among them shall not become a burden to the … community,” he really had no cause for concern. Jews take care of Jews.

Jews came to Syracuse in the middle of the 19th century. Just as they founded synagogues, schools, and communal organizations, they also created social welfare organizations to look after those who could not look after themselves. There were many such organizations: widows and orphans funds, mutual assistance organizations, organizations to visit the sick, bury the dead, feed the hungry, lend to the poor. As B.G. Rudolph puts it in his invaluable history of Syracuse Jewry, From a Minyan to a Community, “every time a new need was discovered another society was formed.” Rudolph noted that there was “much duplication and overlapping,” and in an age without telethons, social media or development professionals, solicitation was door-to-door.

Eventually, there were so many requests for financial assistance from so many worthy entities, including national organizations and European yeshivot, that some citizens of means wearied of being constantly asked for donations and decided to attempt to bring order to the situation. In 1891, the United Jewish Charities of Syracuse was created with the aim of combining as many of the smaller organizations as possible, reducing the multiplicity of fundraising requests, and furthering the goal of Americanization by assisting “the Jewish immigrant to find his place in America.” The collective organization met with mixed success, as many leaders of small organizations chose not to give up their positions and some of the needs of the more recently-arrived Eastern European immigrants (e.g., a mikvah, kosher food) were not shared by the now-established German immigrants who had preceded them and whose Jewish worldview was significantly different.

World War I brought about a major change in the Syracuse Jewish community’s collective fundraising efforts. Urgent appeals for funds from Europe and Palestine resulted in a redefinition of communal obligation and a restructuring of communal fundraising. No longer was the goal of financial support either the integration of Jews into American society or their adaptation to it. A much larger goal became the unification of the Jewish community and the fulfillment of their Talmudic obligation to fellow Jews throughout the world. In 1914, the United Jewish Charities of Syracuse changed its name to The Federation for the Support of Jewish Philanthropic Societies. By 1918, the name was changed yet again to The Syracuse Jewish Welfare Federation. A new era had begun.

“There is no finer page in the history of Syracuse Jewry,” writes Rudolph, “than the story of the Syracuse Jewish Welfare Federation. Unlike the building of the temples and synagogues, the educational institutions, and the charitable organizations which were undertaken by groups who nourished different ideologies, the Federation has acted as a leveling device. It brought together the Jews of German origin and the Jews from Eastern Europe, the Jews who adhered to Reform and the ultra-Orthodox, the professional and the day laborer. It brought out the finest of the men and women of each calling. Many people gave of their time and their means in behalf of the Federation with a devotion and fervor unmatched by any other institution in Jewish life.”

Organization was key to the new Federation’s success. The campaign was organized to last one week. Captains headed divisions of ten workers and met daily for lunch to review their progress. On the final Sunday of the campaign, Federation officials H. Hiram Weisberg and David Holstein and attorneys Gerson Rubenstein and William Gerber hired a horse and buggy and drove around the Jewish neighborhood. They stopped on the street corners and delivered their spiel, telling all listeners that all Jews should be members of Federation and contribute to the cause. At the end of the day, they had garnered $3000 for the cause. These funds were added to others solicited in less novel ways and at the end of the one-week campaign, a total of $32,771 had been raised from 1731 donors, far surpassing the original goals of $25,000 from 1500 donors. The Federation began on a high note.

II. The next chapter: 1928 – 1938

In the first half of the 20th century, Jewish community federations around America were focused almost exclusively on meeting local Jewish needs and concerns – health care, child welfare, assistance for the handicapped, and homes for the aged. Federations also helped to establish Jewish community centers and educational and vocational training programs. Their primary goal was the assimilation and Americanization of the immigrant Jewish population into the larger community. Syracuse was no exception.

But raising money is time-consuming, leaving less time for actually serving those in need. To resolve this dilemma, the Federation for the Support of Jewish Philanthropic Societies of Syracuse made the decision to partner with the Syracuse Community Chest. In so doing, the Federation was relieved of the need to fundraising independently. An article in America’s only Jewish daily published in English, The Jewish Daily Bulletin, reported that “The Syracuse Jewish Welfare Federation was reorganized Tuesday night on a democratic and efficient basis permitting closer cooperation with the Community Chest which makes allotments to a number of local welfare agencies, and also providing for support from the Jewish Community for national and overseas causes. In addition to distribution of funds, the new Federation will also deal with local and national Jewish problems and public relationship.”

A review of the Community Chest first budget in 1922 shows the range of social welfare activities supported by the Jewish community at the time. In addition to the 13 agencies of the Federation itself, there were other Jewish organizations that received direct support from the Chest. Under the category of “Character Building and Recreation” were the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Associations; other “Unclassified” support was provided to the Council of Jewish Women, the Free Bath Association, the Friendly Inn, the Hebrew Free Loan Association, the Hebrew Fresh Air Fund, the Jewish Communal Home, the Jewish Home for the Aged, the Syracuse Hebrew School and United Jewish Charities.

But with benefits of Chest affiliation came complications. As the national economy headed toward the Depression, the Community Chest asked its beneficiaries to cut their budget proposals and decided to cease supporting certain organizations, among them the Hebrew Free Bath (the mikvah), the Hebrew Free Loan Association and The Friendly Inn, which helped itinerant Jews. As a result of these cuts, which mainly affected Russian and Polish Jews, many Jewish donors cut their support. The Community Chest complained that it was giving more funding to the Jewish organizations than it was receiving in donations. Clearly, some reorganization was in order.

External forces in Europe, meanwhile, were jeopardizing Jewish lives. Nationally, federations joined with overseas agencies like the United Palestine Appeal and the Joint Distribution Committee to rescue and rehabilitate Jews living in distress. The National Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Funds, an umbrella organization for federations, was formed in 1932. In response to Kristallnacht in 1939, the United Jewish Appeal was formed, combining the national fundraising efforts of the UPA and JDC. In Syracuse, the cumbersome early name of the Federation was shortened to “The Syracuse Jewish Welfare Federation” in 1935.

While the early work of the Federation had been to help Jews living in America, it soon became clear that emergent needs abroad needed to be addressed. H. Hiram Weisberg, a self-made industrialist and civic leader, who had headed the very first Federation fundraising campaign, was once again called into service to raise funds for overseas relief. The Joint Distribution Committee German Relief appeal, the Jewish Agency for Palestine, the Hebrew University and other non-local Jewish activities were the beneficiaries of a mass drive in 1933. The campaign goal was $15,000.

The sense of urgency could hardly have been greater. Speakers stressed that “at this time, when Jews in Germany are objects of persecution and boycotts, there is need more than ever for the wholehearted cooperation of the entire community to administer financial aid to those unfortunate brothers across the seas.” Aware of the Depression in this country, they nonetheless declared it “insignificant when compared with the sufferings which our fellow Jews have been forced to undergo under Nazi persecution in Germany. There thousands of men, women and children are starving and without clothes or shelter.” Even T. Aaron Levy, president of the Americanization League, joined in urging support of the Federation campaign, saying “the Jews of Germany, with clenched lips, with sublime courage and with patient step, face their destiny. They are doing this in the faith that for 20 centuries Jewry has faced every test without flinching.”

III. Federation and WWII: 1938 – 1948

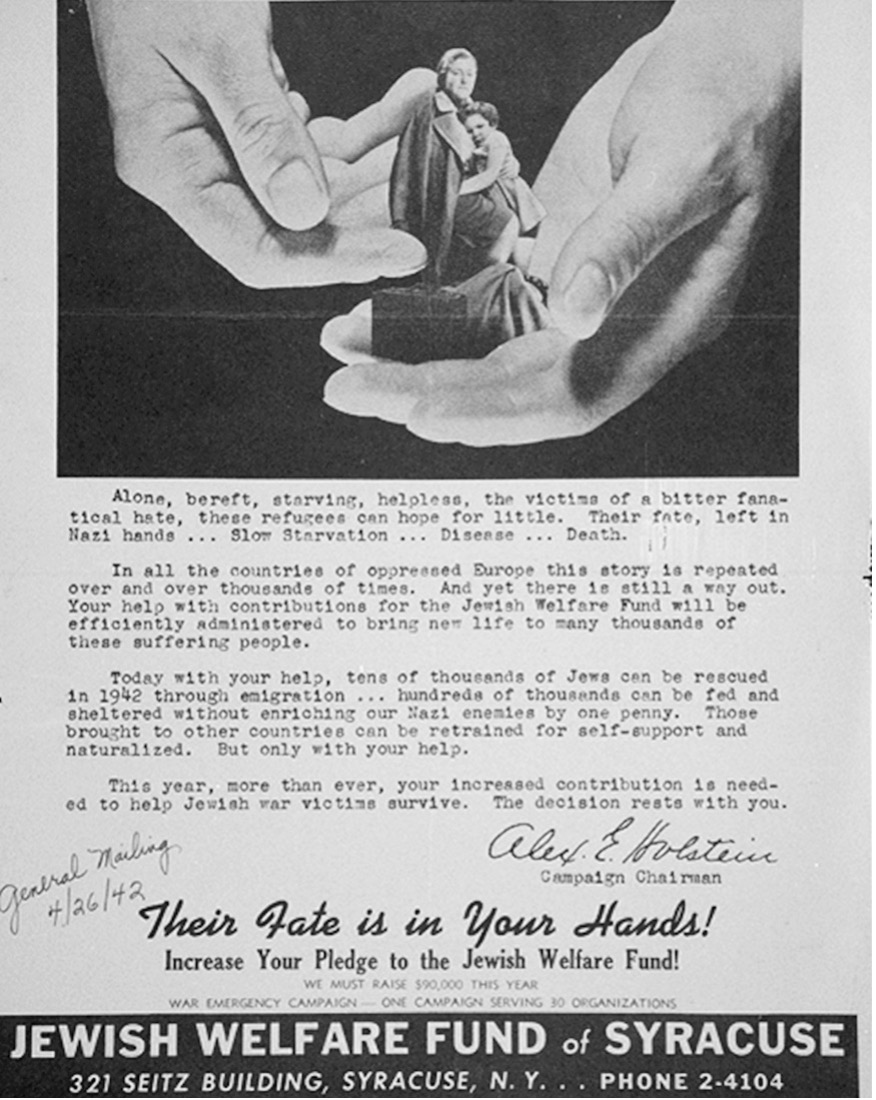

In 1941, the Jewish community was still unaware of the magnitude of the Holocaust, the systematic German extermination of the Jews of Europe. In 1942 the Jewish Welfare Federation launched “one of the most important campaigns in the history of Syracuse.” The campaign stressed that “five million Jews living in Nazi-conquered nations are without food, clothing, shelter and medical care. It declared “The Jews of America are still free to live and free to give” and that their financial support was desperately needed.

“Their fate is in your hands,” said a poster in 1942 advertising the Jewish Welfare Fund of Syracuse’s War Emergency Campaign. “Alone, bereft, starving, helpless, the victims of a bitter fanatical hate, these refugees can hope for little. Their fate, if left in Nazi hands….slow starvation, disease, death.” And yet, it told the community, “there is still a way out. Your help with contributions for the Jewish Welfare Fund will be efficiently administered to bring new life to many thousands of these suffering people. Tens of thousands of Jews can be rescued in 1942 through emigration…hundreds of thousands can be fed and sheltered without enriching our Nazi enemies by one penny.”

As further details of the horrors of the Shoah began to emerge, the Federation stepped up its efforts to help those who survived. At the 1946 Federation Annual Meeting, an oil painting by Syracuse artist David Perlmutter was displayed. Entitled “A Survivor’s Nightmare of the Warsaw Ghetto,” it portrayed a group of Jews huddled near the shattered remnants of a synagogue, looking piteously at a row of eerie Wehrmacht skulls. The painting was to become part the national campaign to raise funds for survivors, refugees and displaced persons. The artist told Federation supporters that these figures represented “survivors of the most diabolical and calculated inhuman assault on civilization” and that he meant the painting “to live as a reminder of what despotism, bigotry and totalitarianism stands for.”

At another meeting, Federation solicitors were told that “Americans alone have the resources with which to do this work of mercy and necessity.” 1946, it was emphasized, was for the majority of the surviving European Jews “the year of decision…. the year in which you will decide whether they shall live or die.” For the starving Jews of Europe, it was stressed, “America is more than a symbol of democracy—it is their last and only hope of life.” The speaker added, “Moreover, there is a special charge upon our consciences to rescue the Jews on whom Hitler “whet the knife with which he intended later to cut the throats of all of us.”

Unable to do anything for those who had perished, federations across the country redoubled their efforts to aid survivors. Hundreds of thousands of Jews, unable or unwilling to return to their former homes in Europe, sought instead to go to Palestine or the United States. In Syracuse, the Federation galvanized the community through well-organized fundraising campaigns that supported refugee resettlement and support for Israel. “Don’t let the light go out,” proclaimed a 1947 campaign poster. “There are thousands of children who have survived Hitler’s plans for their extermination. Sad, hungry, terrified children who need your help. Can you refuse them?” Syracuse Rabbi Irwin Hyman, who served as chaplain and advisor on Jewish affairs to the European theater, returned to Syracuse to tell people about the situation in Europe. “Europe today is fraught with fears—fear of famine, fear of disunity and fear of another war,” he said, adding that “the people in Europe feel that the war had failed to settle many things, and they harbor suspicions that another conflict is imminent.” The need to rescue the Jews who survived Hitler was desperate.

At a 1948 Federation rally in Syracuse, a UJA speaker told the audience that “the survivors of the Holocaust have been ready for months to go to Palestine. They have been attending schools set up in the camp, have been learning trades and have prepared in every way possible so that they will be productive citizens of Palestine. These are the people who, a year ago today, were fed like infants with spoons – such was their physical condition.”

In the years following the war, American Jews became the most important Jewish community in the world. Federation stood in the forefront of helping Holocaust survivors, aiding the nascent State of Israel, and sustaining a meaningful Jewish way of life in America.

IV. Federation and the State of Israel: 1948 – 1958

When the State of Israel was born in 1948, Syracuse Jewry reacted with the same exhilaration as did Jews everywhere. The 1948 Federation campaign proclaimed, “This is the year of destiny for the Jews.” The campaign raised more than $1 million for the UJA.

But Israel was not an easy sell. A major challenge was laid out at the inaugural rally of the 1948 Syracuse Jewish Welfare Appeal. One of the speakers told the Syracuse audience of 1,500 of the indomitable will of the Jews of that nation to fight to the death, if necessary, for their liberty and freedom. “I want to allay some misunderstandings,” he told his audience. “I don’t want the people of Syracuse and of America to think for a minute that, because of some diplomatic expediencies, we Jews of Palestine are ever going to give up our fight. Our people have been let down many times in their history,” he stated, “but we will survive now and, we will win this war. There is not a single Jew in Palestine who believes we will lose.”

At a campaign rally two years later, a Syracuse businessman, just returned from Israel to provide a first-hand account of conditions there, called the people of Israel “miraculous.” He described the present generation as “fertilizer working to plow itself under so that its children may grow.” He named immigration and housing as the major problems of Israel, saying that “thousands of persons in rags have poured into Israel from 40 countries. It’s anticipated that 150,000 will come this year. But immigration really depends upon how many Jews are driven out of Arab-controlled countries,” adding that “the Arabs are forcing Jews to go to Israel to put greater burden on the new state and break her by economic war.”

Former assistant Secretary of State Major John Hilldring, whose United Nations work helped produce the free Jewish state, also addressed the capacity audience: “I don’t understand this worry about another war in Israel. Don’t worry about the people of Israel on the battlefields. They can take care of themselves. Instead of tackling phantoms, friends of Israel should do something about the immigration problem. Most of all they should send money. Only because of the shortage of a few dollars, 100.000 people who have reached the Promised Land are still spending long and weary days. For a few dollars they could be happily resettled.”

Another speaker asked: “In this tragic hour, in this year of our need, what are you prepared to do?” He continued: “We have made two mistakes. At first we feared too little and hoped too much. Then we overestimated our supposed friends. Don’t let us make the third mistake of caring too little. We Jews must do our share. We must do it soon enough and in a big enough way to answer the call of our people in Europe and in Palestine. We must emulate in spirit those Jews of the Holy Land who would rather die on their feet rather than live on their knees. Their destiny—and the destiny of those haggard souls in the DP camps—is our challenge.”

With those ringing messages before them, the Jewish community of the city promptly made plans to set a record goal for the annual Federation fundraising-campaign.

Throughout the decade, Federation emphasized the urgent need for funds for the young state. In 1955, it informed contributors that “the people of Israel, with all their resourcefulness, their energies and their dedication, are racing against time. Their economy must be stabilized, their irrigation projects completed, their immigrants of various cultural backgrounds integrated as quickly as possible. In a critical hour when the Arab nations refuse to lessen their hostility toward Israel, Israel’s people know that tomorrow’s tasks must be accomplished today.”

In 1959, the Federation launched a special fund drive to address what was called “the greatest immigration crisis in a decade,” to provide for transportation, initial absorption and settlement of immigrants to Israel. Federation’s Women’s Division worked particularly hard on the project, believing that “only the swiftest and most substantial response on the part of all the Jewish women in the community will make it possible for Israel to meet the new demands.” “ANSWER THE CHALLENGE, WOMEN OF SYRACUSE!” they exhorted. To emphasize their determination to succeed, they announced a citywide house-to-house solicitation to reach every Jewish woman in the community for her individual contribution.

V. Helping at home and abroad: 1958 – 1968

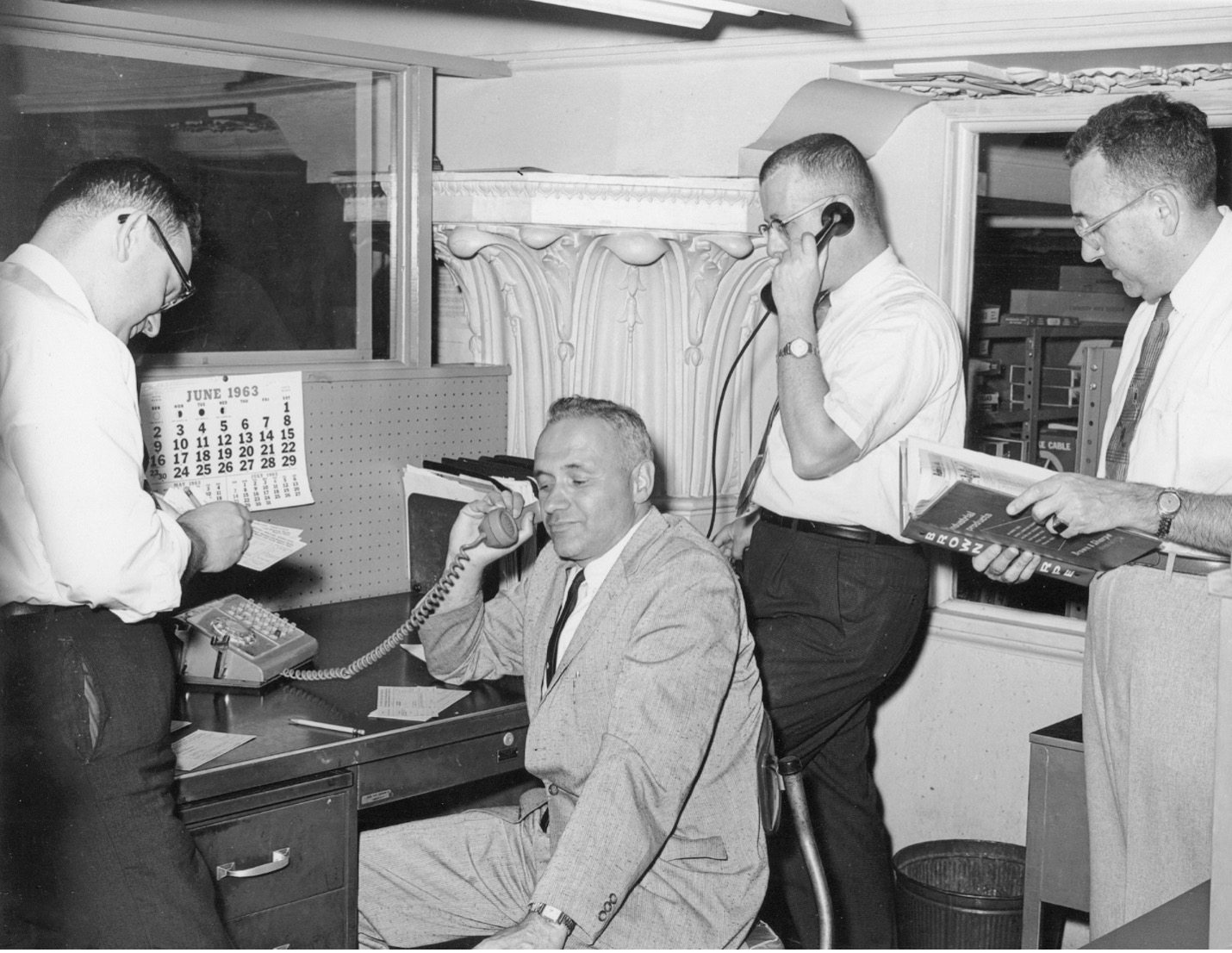

Contributing to the Federation’s annual campaigns became a mark of Jewish identification for many. Campaign workers and donors continued to be involved in the work of the Federation during the 1950s and 60s. But contributions to the annual campaigns declined and, at one point, Federation even had to borrow money to send to the United Jewish Appeal.

In 1958, the UJA national chair spoke at the Federation’s Initial Gifts meeting. “Israel is Jewry’s answer to two thousand years of Jewish homelessness and persecution,” he said, noting that the Syracuse Jewish Welfare Federation and the UJA were both celebrating their 20th anniversaries. “Through the years,” he pointed out, “funds from Syracuse have rescued 5,732 Jews.” This year, he added “Syracuse’s goal will be 500 lives.”

By 1963, the Federation role as the representative of the entire Jewish community became more prominent. It began to make its voice heard on a variety of local, national and international issues. A resolution was addressed to President Lyndon B. Johnson, in the name of Federation, stating that it approved of the march from Selma, Alabama, on behalf of civil rights. A resolution supporting the integration of Syracuse public schools was addressed to the Superintendent of Schools and to the Board of Education. A delegation of members of the Federation Board went to Washington, D.C., to be present at the “Eternal Light Vigil” protesting the treatment of Jews in the Soviet Union. In February of 1967, it was decided that Syracuse Jews would devote a weekend in March on behalf of Soviet Jewry, with special services to be conducted in all temples and synagogues, and a mass community rally at Nottingham High School auditorium.

Concern for Israel still dominated the Federation agenda. An Israeli diplomat reported at a dinner meeting of the Syracuse Jewish Welfare Federation that immigration to Israel would continue at a high level for the next five years. “At least 200,000 newcomers are expected from distressed areas,” he reported, warning that a “second Israel” of permanently poor and unintegrated immigrants could become a grim reality unless special efforts were made to accelerate absorption of the newcomers. “The full absorption of these groups is a very difficult task which must be handled with great skill, more social workers, more teachers, youth centers, adult education facilities, and just about everything else which more money will buy,” he declared. Furthermore, he stressed, “large numbers of immigrants from certain underdeveloped countries are illiterate, and everything humanly possible must be done to lift them culturally and economically.”

Senator Abraham Ribicoff, speaking at another Federation campaign kickoff meeting, told the audience that “American Jews should guard against too sentimental an approach to the problems of modern Israel.” Ribicoff said that “American Jews commonly have an unrealistic conception of Israel, despite the fact that the Jewish nation is besieged with many serious problems. Most visitors see too much good when they get to Israel,” Ribicoff told the audience. “There’s a tendency to over- sentimentalize during visits to the country.” In reality, he said, “Israel, a nation of about 2.5 million people, suffers from an imbalance of $500 million in its trade setup. That means that Israel imports $500 million worth more of goods than its exports. For a nation the size of Israel, this imbalance represents a serious threat to economic stability.” In addition, the senator continued, “Israel also spends the largest percentage of any nation in the world today on defense—about 12% of its gross national product. The United States, in contrast, spends only about three per cent of its gross national product for defensive purposes.” The reason, Ribicoff said, is that Israel “is surrounded by nations that would just as soon wipe it from the face of the earth.”

As the Federation completed its half century of service to and on behalf of the Syracuse Jewish community, it had much to be proud of. As an editorial in the local paper pointed out, the Federation was a strong unifying force for the Syracuse area Jewish community, noting that “we can see the concept at work in the centralized fund raising effort each spring to develop and expand agency programs for families, for cultural and recreational activities, for summer camping and Jewish education.” With great insight, the editors noted that Federation represented “Judaism in action and Judaism is inherently and deeply a religion of action, a way of life, a way of living.”

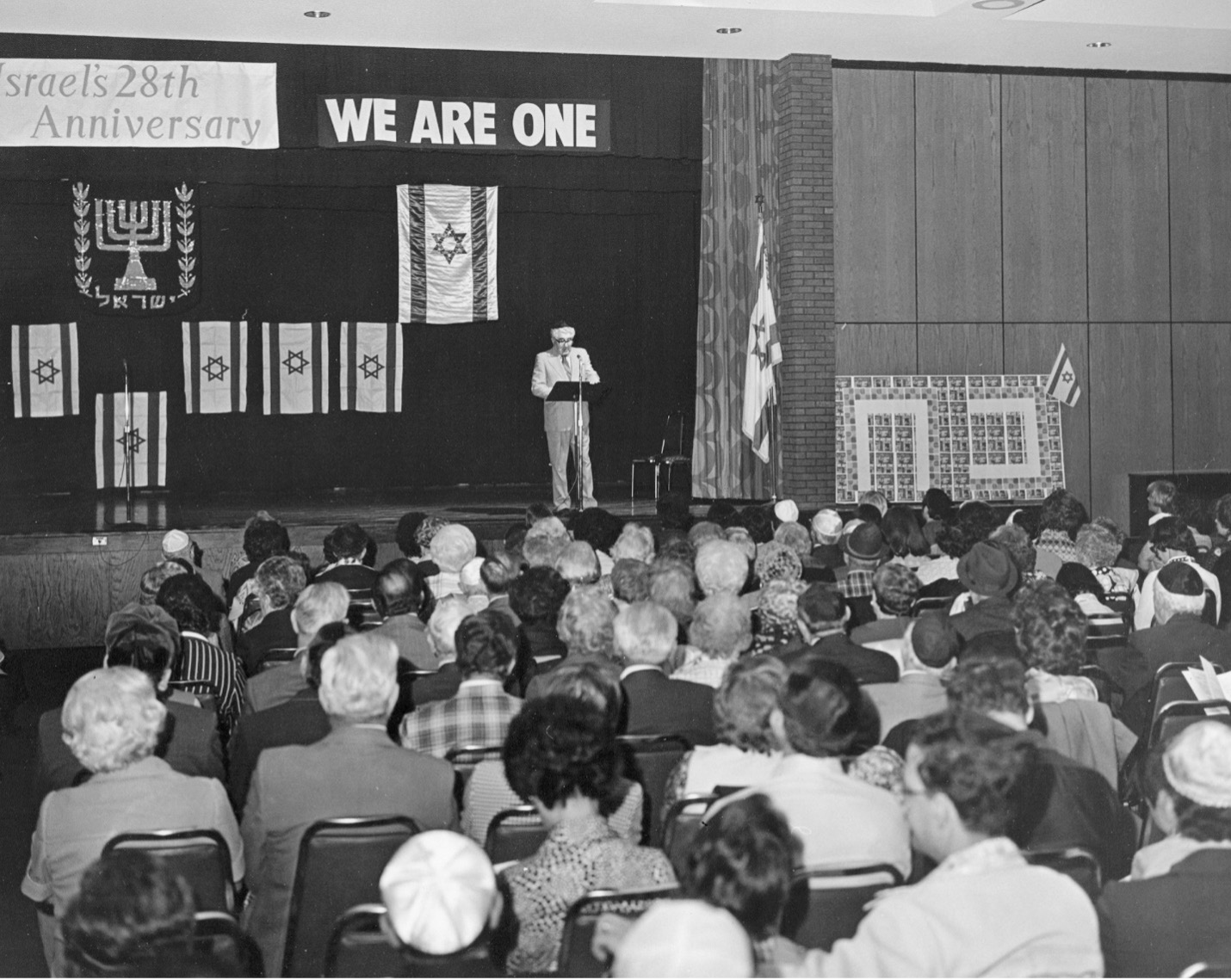

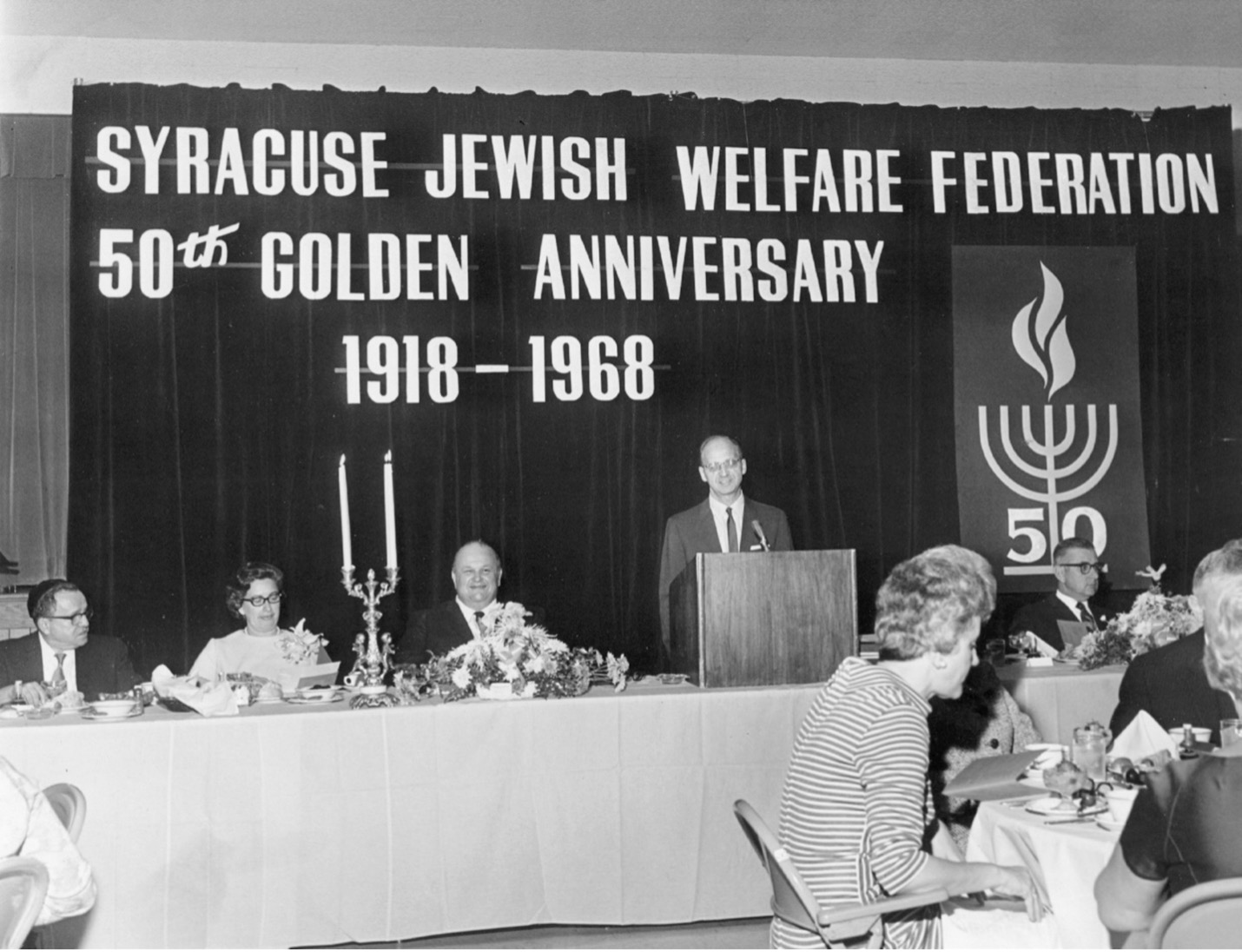

VI. Federation’s 50th Anniversary: 1968 – 1978

On the occasion of the Syracuse Jewish Welfare Federation’s golden anniversary in 1968, the Syracuse Herald Journal offered its congratulations, noting that the guiding principle of the Federation for 50 years “has been the Jewish concept of tzedakah.” It explained that “tzedakah is more than charity. It is more than philanthropy. It is more than man’s humanity to man. It is righteousness and justice, commodities that we all need. It is the highest ideal in Jewish teaching for it is the highest application of Jewish ethical values.”

Although rejoicing in its successes, the Federation never lost sight of its mission. In 1969 it took out a full page ad in the local paper, reminding the community about the 1967 Six Day War. “A year and a half ago,” it stated, “the entire world watched as Israel, standing alone, valiantly and successfully defended her freedom against armies sworn to destroy her.” But it made the case that the war was not over: “Israel’s 6-Day War is fought every single day of every year she exists. It is a war of constant armed vigilance against attack. Of maintaining peak military strength to deter invasion attempts. Of saboteurs infiltrating her borders regularly to plant mines that kill and maim civilians. Of artillery attacks across her borders. It is a battle in which children must sleep in bomb shelters and farmers carry weapons to the fields.”

Israel’s war, declared Federation, was “a constant war to absorb a backlog of 300,000 refugees who need to be taught a trade, settled in homes and be made a part of the life and economy of the country. It is a war against arid land that must be irrigated and cultivated if the people are to be fed. It is a war to find the resources and people to teach the young and care for the old and ill.” “This other war is our war,” said Federation. “Through contributions through Federation to the United Jewish appeal, we help the immigrants become productive citizens. We cultivate the land, teach the young and care for the old.” Urging donors to give generously, they concluded: “Let’s win our war.”

But while the United Jewish Appeal (UJA) continued to be the largest beneficiary of the Federation’s philanthropy, the local community continued to receive great support. The original beneficiaries of the Jewish Welfare Federation at its founding in 1918 were the Jewish Communal Home, United Jewish Charities, Jewish Fresh Air Camp, Ladies Aid Society, Council of Jewish Women, the Hebrew Free School, the Jewish Home for the Aged and the Jewish Orphans Asylum. Fifty years later, support had shifted as the Jewish community grew increasingly suburban and affluent. The Jewish Community Center and the Jewish Family Service were now supported by Federation, as was Hillel at Syracuse University and the mikvah.

Federation also supported a number of new initiatives. It co-sponsored (with B’nai Brith) a locally produced Jewish television program called “Jewish Journal” that debuted on the first day of Passover in 1974. It gave financial support to the Syracuse Hebrew Day School, which had opened in 1960 and to the Rabbi Jacob Epstein High School of Jewish Studies, which opened in 1970. It also sponsored the creation of a supplementary school for Jewish children with mental retardation. It brought Israeli high school students to the community to meet with their peers and continued to bring speakers to the area for many informational and educational programs.

Federation’s influence in the larger community on national and international issues could also be seen in the wording of a local editorial condemning the U.N.’s “Zionism is racism” resolution. The paper wrote: “The deadbeat members of the United Nations have spoken. By a vote of 72 to 35 with 32 refusing to vote, thereby silently endorsing the decision, the General Assembly equated Zionism with racism. The Communist nations and their friends, those in the Arab bloc and the so-called Third World countries carried this resolution to the floor of the Assembly. As the Syracuse Jewish Federation pointed out, only 24 of these countries are democracies. Among them is Israel, the one democratic country in the Middle East.”

Federation’s continuing efforts to educate the general public about issues of grave concern to the Jewish community could also be seen in its publication of a 16-page supplement to the Sunday Herald-American of “THE RECORD,” a documentary of “all the terror and tragedy of the Nazi years.” The publication was intended to provide factual background to 96 hour television drama entitled “Holocaust.”

VII. Federation and Soviet Jewry: 1978 – 1988

In 1978, the Federation board voted to support the creation of an “Anglo-Jewish newspaper in Syracuse.” Its purpose was to “help surface the potential of our community” through information, education and entertainment. “In performing these basic functions,” the Federation averred, “the JEWISH OBSERVER adds a vital element of cohesion to our community. It will give groups and organizations a better understanding of each other, and demonstrate how separate pieces fit together to form a larger picture.”

In 1980, the Federation’s executive director stated: “The single most significant fact about Jewish Federations is that they are voluntary bodies, created and perpetuated by volunteers who determine their philosophy, objectives and programs. Our concerns encompass the total Jewish community and our responsibility is to the welfare and security of every Jew in Syracuse.”

Federation defined itself as “the central, representative planning body of the Jewish community in the Syracuse area.” It published Federation News, sponsored “Jewish Journal,” a weekly television program, and established commissions on the Jewish elderly, Jewish education, and the Middle East. Federation often brought important Israeli statesmen, such as David Ben Gurion, to Syracuse to bolster support for the Jewish state. Super Sunday phone-a-thons, begun in 1981, became a hallmark of Federation fundraising. So successful were the hundreds of callers at the phone banks that follow-up sessions were called Magnificent Monday, Terrific Tuesday and Tremendous Thursday.

Resettlement of Jews from the former Soviet Union became a Federation priority in the 1980s. Jews were not allowed meaningful Jewish communal life in the Soviet Union, although they were referred to and considered themselves Jewish. In the 1980’s hundreds of refugees began to settle in the greater Syracuse area once the “gates to freedom” were opened by the former Soviet Union. These refugees were settled and absorbed into the Jewish community through the assistance of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and under the guidance of the community’s own Russian Resettlement and Acculturation Program. The Federation, Jewish Family Service, the Day School and the area’s synagogues all took leading roles in integrating the newcomers into American Jewish life.

On December 6, 1987, the Syracuse Jewish Federation and thousands of concerned citizens from across the nation travelled to Washington on the eve of a meeting between Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President Ronald Reagan, to tell the Russian leader to “Let our people go!” “Freedom Sunday,” as it was called, drew 250,000 protestors, including the contingent organized by Federation. The calls for a “Second Exodus” of Soviet Jewry were, one commentator noted, “one of the great peoplehood actions” of Jewish history.

The 1987 appearance of the Moscow Ballet in Syracuse was the occasion for the publication of a letter by the Federation’s vice president for community relations in the local paper. He wrote: “The performances by this company remind us, all too painfully, that the cultural freedom allowed these artists is denied to Jews in the Soviet Union. The Soviet government deprives its Jewish population of cultural freedoms which are granted to other groups in the Soviet Union — freedoms that we as Americans take for granted. By denying them their cultural freedom, the Soviets seem intent on obliterating Soviet Jewry as a cultural entity. They have suppressed Jewish theater and music, and have prohibited the establishment of Jewish libraries and cultural centers. Soviet Jews are denied the right to practice their religion, to study their culture and ancestral language. Jewish schools and synagogues have been shut down, and Hebrew teachers have been imprisoned. Rather than live under these intolerable conditions, about 400,000 Jews have expressed their desire to emigrate to Israel, where they can live freely as Jews. In recent years, however, the Soviet government cut emigration down to a trickle. All too often, those who express a desire to leave are deprived of their jobs, denied medical assistance, and otherwise harassed and terrorized. In this age of glasnost, we find it hard to reconcile increased, and welcome, opportunities for cultural exchange with the continued repression of religious and cultural freedom for Jews in the Soviet Union.”

Federation took public stances on other international issues. Federation leaders published a letter in support of President Reagan’s raid on Libya, saying “The Syracuse Jewish Federation Inc. commends President Reagan for his decisive action in ordering the recent attack on terrorist targets in Libya. It is hoped that this action presages a sustained and purposeful American policy against international terrorism.” Other issues, including talks with the PLO received considered Federation responses and kept the Jewish community’s positions in the public eye.

VIII. Facing Our Future: 1988 – 1998

Federation’s 70th year coincided with the 40th anniversary of the founding of the State of Israel. To mark the occasion, Federation sponsored IsraFest, a day-long series of events emphasizing the remarkable accomplishments of the Israeli people. Exhibits, dancing, games, videos, a sampling of Israeli food, songs and more were designed to acknowledge the courage and the hard work, the faith and determination that over four decades served to build the vibrant but beleaguered state of Israel.

Federation’s Young Leadership program underwrote missions to Israel, believing that a Mission to Israel was one of the most important experiences every member of the Jewish community could have. The goal of the missions was to make the history, beauty, tastes, sounds, current events, magic, and wonder of Israel come alive for participants.

Federation members themselves travelled on missions to the nation’s capital to discuss priorities with legislative leaders and lobby on behalf of issues important to the Jewish community. They learned from leading analysts, thinkers, scientists, and political and military figures, as well as getting an inside look at how Federation implements its goal of uniting and caring for Jews around the world. A rally in Syracuse to display solidarity with Soviet Jewry drew 500 attendees. A political scientist and Soviet scholar told the audience that “the status of a population like the Jews – who have historically been scapegoats – is so uncertain that it would be in the best interest of that population to leave.”

But despite success in the political and social arena, as the 20th century drew to a close, the Federation found itself in a difficult situation. The American Jewish community had changed. Increasingly, assimilation and intermarriage took their toll, and many Jews were uninvolved in Jewish life. They had no desire to use Jewish institutions even for rites of passage and had insufficient interest in Jewish causes to contribute money. Burdened with underachieving campaigns and depleted cash reserves, the Federation and its beneficiary agencies faced severe fiscal and existential challenges. “Downsizing” and “consolidation,” words no one liked to hear, were being used more and more often. In 1995, a group of Jewish community leaders from Federation, agencies, synagogues and other community groups began a multistage process to try to understand the new Jewish community ethos, collect data on community priorities, identify issues and establish guidelines and recommendations for the future. Entitled “Facing Our Future,” the group sought as broad a community response as possible. Meeting space in the Onondaga County War Memorial was arranged to accommodate the hundreds of individuals who came to participate in three public forums.

Four task forces were established on community cooperation and coordination, Jewish identity and continuity, growing older and Jewish youth. Issues raised included community finances, fundraising, Jewish education including religious schools and the day school, the potential for collaboration in programming and facility usage, social service needs, service delivery, the possibilities of reducing duplication of services, the availability of physical and mental health services, Jewish residential services, etc. The information that was gathered was consolidated, reviewed and discussed over many months and a final series of recommendations were made to all Jewish community agencies, organizations and synagogues.

The Facing Our Future final report stated that “for one of the rare times in the life of our community, we have been given an opportunity and the responsibility to effect the kinds of changes that will carry us into our future and the future of our children. The choice is ours, whether we fall prey to our own past defensiveness and fears or instead move forward, carried on by new and promising ideals which will both help to secure and strengthen our community.” The report called for consolidation of staff, reduction of the costs of service and program delivery, and limitation of expenditures in line with revenue. Its proposals sought to combine and realign the delivery of specific services “in the most efficient and effective manner without sacrificing quality and, in some cases, improving quality and expanding services.”

As the 20th century became the 21st, the Task Force stressed that “time is not our ally” and called for the “functional reorganization of our services, without any interruption of their quality.” It was a call to action, emphasizing that failure to change “only the innocent and unprotected will be hurt.” Instead it declared that “our only hope is one of a perpetual leadership which ensures that all the hard work we must start to do today will not go for naught.”

IX. Turn of the Century: 1998 – 2008

Federations and fundraising have always gone hand in hand. It has been said that Jewish leaders receive their basic training in the trenches of fundraising and the effectiveness of lay and professional leadership has always been measured by their success at solicitation. Involvement in fund-raising provides volunteers with a fundamental understanding of Jewish communal needs and has encouraged many to become more involved in the Jewish life of their community. The annual campaigns, the work of sectors like the Maimonides Society and Women’s Division, and Federation Super Sunday phone-a-thons were annual fundraising activities which generated most of the budget for the Federation and its constituent agencies and organizations. All of them required a lot of planning and an abundance of willing volunteers.

But fundraising is hard and, at times, thankless work. At the start of the 21st century, it had become apparent that new mechanisms were needed to provide the financial sustenance that so many Jewish organizations required from the community at large. Thus, in 2001, the Jewish Community Foundation was established by the Federation. Its financial mission was “to ensure the continuity of Jewish life in Central New York into the future.” Its goals were to provide donors and their philanthropic Jewish interests with opportunities for giving that were simple and meaningful, to serve as the local depository of endowment funds for the entire Central New York Jewish community, to assist donors in identifying programs and organizations that could benefit from endowment funding, to create a philanthropic environment to make giving relevant and meaningful to people of all ages, to function in a manner consistent with the best principles, traditions, and teachings of the Jewish people and to operate with support from and support for the Syracuse Jewish Federation. The Foundation would become one of the Federation’s greatest successes.

As the 20th century ended, Federation reevaluated its mission, making sure that it was consonant with the needs of the community in the modern age. Its purposes had evolved from its inception in 1918, and reflected a more global consciousness and an enhanced awareness of its leadership responsibilities. No longer was it just a social service funder for the community, no longer a mainstay of the Israeli economy, no longer just an advocacy group. Its roles had become significantly broader and its range of responsibilities significantly greater. The 21st century Federation was responsible for:

- Maintaining links with and supporting the national Jewish community of the USA, Israel and every part of the world

- Building a thriving Jewish community and enriching the educational, cultural and social life of the Jewish community

- Raising funds for the support of overseas, national and local Jewish philanthropic agencies

- Providing for central planning, coordination, administration and leadership development for local Jewish communal services

- Safeguarding and defending the civic, economic and religious rights of the Jewish people

- Representing the Jewish community in inter-religious and inter-group activities

- Ascertaining the will of the Jewish community on matters affecting the total community and acting as its spokesperson in such matters.

As the new millennium began, Federation sought ways to meet the challenges of a new era. It was aware that it was a known and trusted organization, with the effective financial stewardship and oversight of resources that donors required. Federation was a mainstay of local communal life and the major channel for support for Israel and Jews in need around the world. Unlike other umbrella charities, Federation also served as the lead organization for the Jewish community, its advocate and its defender. Federation could respond to a crisis and act as a safety net. As a member of the Jewish Federations of North America, and in partnership with the Jewish Agency for Israel, the Joint Distribution Committee and ORT, Federation was a powerful force both on the American scene and in the global Jewish arena.

Cognizant of its roles and responsibilities, Federation made some significant structural changes in the 21st century. It reduced the size of the Federation board and elected members who represented the Jewish population in Central New York, and worked together to make informed decisions that benefitted the community on a variety of levels. It was clear that a new era was beginning. As a campaign chair noted, “we introduced a new word into the local Jewish community. That word was ‘change’. We changed the old ways that the Jewish Federation did things. We did that by hosting community events and working as a group toward common goals of raising money and more importantly fostering a stronger sense of community.”

X. Federation in the 21st Century: 2008 – 2018

The 21st Century saw the expansion of Federation partnerships not only with its beneficiary agencies but with the community’s synagogues and other Jewish entities. One hundred years after its founding in 1918, Federation continued to work to build community and to ensure the continuity of Jewish life in Central New York by encouraging the participation of all Jews in the region in activities offered by its family of agencies, area synagogues and other Jewish organizations and institutions.

In 2010 the constitution and by-laws of the Syracuse Jewish Federation were updated. At that time, the official name of the organization became “Jewish Federation of Central New York.” The growth and diversification of needs in the local Jewish community continued to be a major Federation focus. At the same time, attention and funding continued to be allocated to those national and international issues that reflected the needs of Jews around the world, especially Israel.

In the 21st century, the Federation no longer considered itself solely a fundraising body, but rather an organization that embodied a 3,500 year tradition of caring, going back to the giving of the Torah. Federation, its leaders said, “is made up of the people who care enough to want to perfect an imperfect world. Federation reflects the passion of commitment, where tzedakah and a sense of social justice can make a difference in someone’s life.”

Federation proudly declares that it is “the one place that belongs to every Jew. It is the place where philanthropy, volunteerism and commitment come together to make a difference—to repair the world (tikkun olam).” Fundraising is still at the heart of Federation’s mission, but Federation is much more than a community financer. Rather, it represents the entire Jewish community of Syracuse in highly meaningful ways in matters local, national and international.

In the polarized political climate that followed the 2016 election, for example, Federation took a public stance against anti-Semitic and anti-Israel statements and actions, declaring that “the Jewish Federation of Central New York is deeply troubled about the rising tide of anti-Semitism in the United States and abroad. We are also concerned about increased virulent anti-Israel statements and actions here and abroad which go beyond differences over policy but rise to anti-Semitism in their scope and degree. We condemn all hate speech and reaffirm our commitment to equality, human dignity, and peace. We condemn attacks on any religious or ethnic groups that share our commitment to equality, human dignity, and peace and hold that an attack on any such group is an attack on us as well. We will continue to be vigilant in identifying all manifestations of bigotry, and we will work independently or with allies to reduce and eliminate their adverse effects on our community. We will respond as needed to acts and words that are in opposition to our mission to protect the interests of the Jewish community and to advocate for the State of Israel.”

The direct beneficiaries of the Federation campaign had changed from 1918. The Free Loan Society, the Orphans Home and the Friendly Inn no longer existed, but the mikvah was still supported as a community asset. The YMHA and YWHA had become the JCC and new institutions arose. The Federation now supports three different community schools and provides assistance to young people through subsidies for Jewish camping and trips to Israel. The Jewish Community Foundation proudly holds assets of over $14 million and together with the Federation has raised more money than ever before, allowing the Federation to greatly increase its support of local institutions.

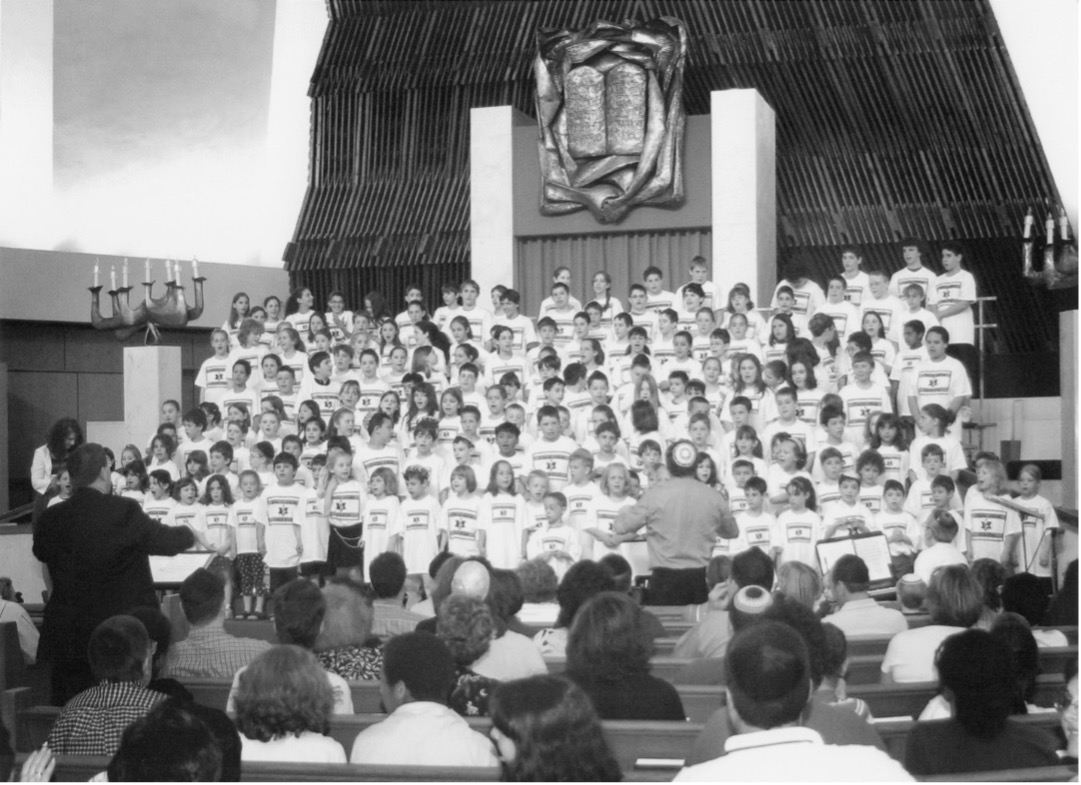

Federation honors the past through the Judaic Heritage Center, the Syracuse Jewish Cemeteries Association and the annual Yom HaShoah/Holocaust Remembrance Day, a community-wide program dedicated to honoring the memory of the victims of Nazi genocide. Federation also brings the community together to celebrate in times of Jewish joy. It supports the community Yom Ha’Atzmaut celebration, the Jewish Music and Cultural Festival and helps bring the Israeli Scouts Caravan to town each summer. As the central address for the Jewish community, Federation hosts the community calendar, publishes the Jewish Observer and emails”Community Happenings.”

Once again, as at its inception, the Federation is focused on meeting local needs. 72% of funds raised support the local community, with the balance supporting over 30 programs for Jews in need all over the world. “We do the good that is in your heart,” is a Federation motto. It has been true for 100 years and will prevail for the next 100 years as well.